“MEETING TONIGHT”

About this Exhibit

MEETING TONIGHT: TWO SOUTH CAROLINA AFRICAN AMERICAN CAMP MEETINGS is an ongoing inquiry and meditation on the spiritual and material experience of early and late African American Methodism in the sacred outdoors.

In 2017, photographer Holly Lynton set her camera to the ritual excitements and solemnities of the annual outdoor assemblies of the Methodist camp meeting tradition in South Carolina. MEETING TONIGHT is a study, then, in the Black sense. Which is to say that MEETING TONIGHT is no colonizing imposition or anthropology project in the name of photographic art, but a thinking-with and -after the human and non-human subjects on view. Study, in this sense, is not an objectification of people and things, nor an approach to them by way of books, but rather embodied thinking. It is, as Fred Moten and Stephano Harney put it, “what you do with other people. It’s talking and walking around with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three…To do these things is to be involved in a kind of common intellectual practice.” Approached humbly, it is, they add, “among other things, a way to think of love.”

MEETING TONIGHT is thus a study in love and love’s Black religious leanings. Together, photographic images and three homiletical meditations convey an emotional history of the African American Methodist camp meeting in South Carolina and materialize a prayer for its undefined future.

Interpretive Homilies

Maurice Wallace is a university professor and clergyperson who has served two North Carolina African American congregations as lead minister. In his homilies, the speculative insights of Black Studies meet Black religious practice in inspired, deep-thinking communion.

The homiletical meditations that accompany the photography of “Meeting Tonight” may be considered across a choice of media.

Each homily may also be heard as an audio file only or text file only as a companion to those perusing the exhibit at their own pace.

Photography Gallery

Holly Lynton is an award-winning fine arts photographer based in Massachusetts. She has attended camp meetings at St. Paul, Shady Grove, Indian Field, and Cypress annually since 2017. Every visit is like a prospector’s dig, like panning for treasures her instincts tell her are there to be uncovered if she is patient enough, faithful enough, and open enough to receive pictures impossible to take.

Interpretive Essay

By Maurice Wallace

The old campground is ritual Black geography, the space of Black gathering where we feel least Black in the sense of being among only ourselves. And yet, being among only ourselves this way, we make ourselves as Black as we have ever been. In the clearing, lush in groundcover, sets the sylvan undercommons. An enduring topos in Black sacred music from the Fisk Jubilee Singers in the nineteenth century to the Mighty Clouds of Joy in the last third of the twentieth, the old campground is at once a physical site—terra firma—and a dreamscape ecology, which, “if you go there—you who were never there—if you go there and stand in [that] place,” the memory of having been there ahead of time “will be there for you, waiting for you,” like it was home.[i] The old campground is liminal space, then, between here and there, then and now; between what has been and what could be if we are brave enough and don’t neglect the annual re-memory of black gathering that has been camp-meeting for as long as anyone can remember. So we sing, as we have always done:

D-e-e-e-p river, my soul is over Jordan.

D-e-e-e-p river, Lord. I want to cross over into campground.

Or with gospel-shout:

Meet-i-i-i-ng tonight.

Meet-i-i-i-ng ton-i-i-i-gth. Meeting on the o-o-o-o-ld campground.

Of course, much has been said and written already about the Protestant revivals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, about the new world movement to grow English Methodism, specifically, and the camp-meeting tradition that developed in the wake of that mission. But what is to be said or thought of the campground itself as the created place of worship and early peoplehood? In that antebellum practice Russell Richey calls “cathedraling the woods” with godly promises and sacred songs, what influence do the sights and sounds of the open air have on the religious and social senses? Better, what is the nature of this ground, this slight toehold in rock face of New World survival, where George Whitehead and Francis Asbury stumbled on wild fowl and fugitive slaves huddled in their bands noising religion already when the Methodists came preaching? How did the teeming woods and winding fields, and their indigenous inhabitants—Black and Native, animal-life and ground-life—encounter the Methodists? What sort of give-and-take between the ecclesial and ecological practices would have brought the peculiarity of slave religion, most expressly, out from deepwoods obscurity into the increasingly airier fields of assembly as life together—the first and last hope of the once-stolen and daily trafficked ones, the gone-missing and the ones defiantly making off on their own?

Tucked away in country fields, tall pines giving their ritual marronage cover, the St. Paul and Shady Grove campgrounds in Dorchester County, South Carolina abide quietly most of the year, out-of-the-way of the anxious comings and goings of everyday southern living. While the mapmaker locates St. Paul Campground properly in Harleyville, and Shady Grove Campground in the county seat of St. George, these old prayer grounds also belong the unmapped milieu (though perhaps not unmappable) of black mystical sound and feeling. Could we imagine a nineteenth-century mapping of the religious intensities of black life in captivity and freedom in the American South? The most passionate expressions of religious feeling would almost certainly overlay the South’s denser terrains away from town in the uncultivated lowcountry of Spanish-moss and tangled brush, piney groves and cypress swamps, of forgotten rice fields where the willfulness of black gathering, expressed in the aural hieroglyphics of deep moanings, fervent shouts, and vernacular prayers of the enslaved, founded the first church in the wild. Out there, over yonder, in the Black outdoors—here, in this here place where so many Black folks near Charleston would become African and Colored Methodists (AMEs and CMEs, in other words), the Black camp-meeting came into being, ritualizing Black reunion as a sacramental practice. The St. Paul and Shady Grove camp-meetings have preserved this annual ingathering of Black life and memory for the full part of a century and a half.

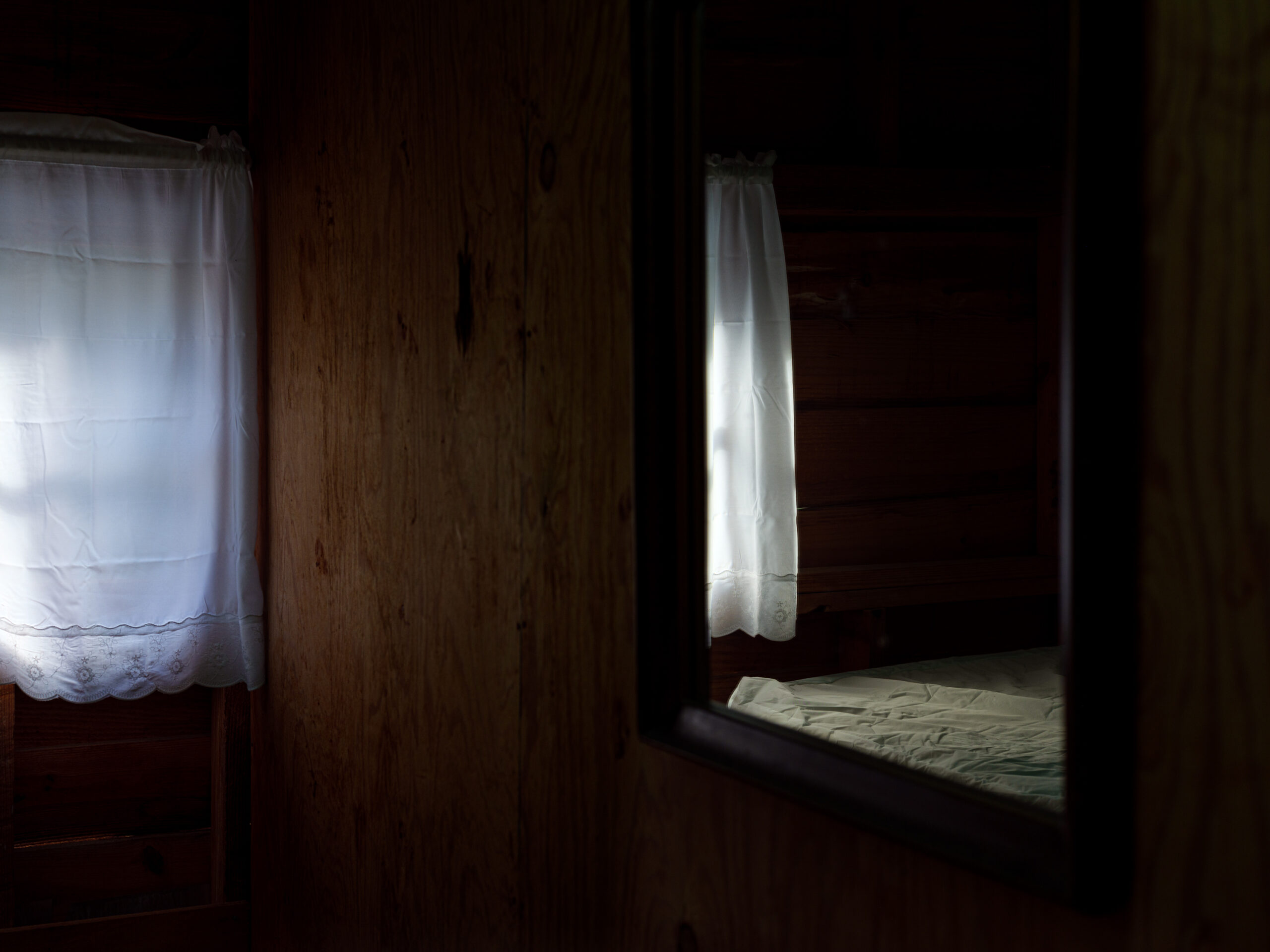

The official history of the St. Paul camp-meeting dates back to 1880 when four Dorchester County freedmen purchased 113 acres of Harleyville woodland, deeding the expansive plot to a board of St. Paul trustees for an independent African American campground. Built around a central “tabernacle”—the name given to the great churchly pavilion where the pilgrim-campers convene for regular services of congregational singing and front-of-the-pulpit preaching—more than fifty austere wooden cabins, referred to as “tents” in camp-meeting parlance (despite their clear similitude to plyboard huts), circle the plywood worship space facing the tabernacle. The tents, which once housed the faithful for an entire week of reunion and revival, today give but daytime shelter to the three or more generations converging on St. Paul daily during the third week of every October, some living in their tents overnight. Two camp stores structurally assimilated into the ring of tents and an ample number of privies set just outside the ring complete the physical facilities for camp-meeting. Still, the experience of camp-meeting at St. Paul or Shady Grove (or the white campgrounds at Cypress and Indian Field) is infinitely more than its built environment. “The site and buildings possess integrity of location, setting, design, materials, workmanship, feeling and association.”[ii] At camp-meeting, the built and natural environments co-mingle with the ritual acts of good religion and Black cultural memory to hallow if not the grounds per se then certainly the singing, whistling, laughing intimacies of Black life together praying, playing, suppering, remembering.

Like St. Paul, the Shady Grove camp-meeting had its beginnings in early in the postbellum period. In 1870, emancipation was young and still uncertain, more rhetorical than real. Caesar Wolf, a Dorchester County freedman, and a small band of others, newly emancipated, were said to have been travelling on the road nearby a St. George rice plantation when a violent weather forced the freedmen into the woods for shelter under a copse of protective trees. Discovered quite accidentally by Sam Knight, the landowner, Wolf and his fellow travelers were promised a parcel of his property in exchange for their help harvesting and thus saving his rice crops from the unusually rainy conditions. Thus did the Shady Grove camp-meetings begin in the pristine sanctuary of trees and ground cover variously denominated brush arbor, hush arbor, bush arbor and brush harbor well before either tent or tabernacle was erected. Later, both were built in the same circular arrangement that set the Methodist fields apart from the start of Wesley’s mission in the colonies. While the tabernacle calls everyone’s notice to the interior life, the tent’s spartan comforts encourage life outside among neighbors—women, men, children, trees, a rock, a river, neighbors all—for meeting.

Meeting Tonight: Two South Carolina African-American Camp Meetings is a visual and homiletical meditation on Black gathering as a sacramental practice in-itself. These photographs by Holly Lynton permit us to see the virtues preached in the tabernacle embodied in and around the tents alive with amusement and feasting and quiet. Here, within the circle that held the one-time Methodist Frederick Douglass, those of us with eyes to see may catch a glimpse of the living memory of the Black outside, that friendly universe of ground- and sky-life a world away from harm, where the wicked cease from troubling and pictures of Black together-life, always already out there, wait to be made material.

[i] Toni Morrison, Beloved (New York: Random House, 1987), 36.

[ii] “St. Paul Campground,” United States Department of Interior, National Park Service, National Register of Historic Places (April 3, 1998)

Digital Exhibition Companion Production Team

Featured Artist: Holly Lynton

Interpretive Text/Homilies: Maurice Wallace

Curated and Produced: Nathan Jérémie-Brink

Video Homilies Production: Stephen Mann

Web Design and Consulting: Maurice West